Hoping nobody would notice: my life with Tourette syndrome

May 17, 2022

My body was bent, my head was down, and I could feel my teeth stinging as I drank from the ice cold water fountain. I was in third grade, and Mrs. Redabaugh, our long term sub, had let me go. The hall was empty, and I thought I was alone. A fifth grader came up to me, quiet as a mouse, and said “Are you the girl that barks like a dog?” I shot up and looked her dead in the eyes. Without answering, I made a b-line for the bathroom. I shut the stall door, and burst into tears. If I had answered her question, I would have said yes.

“You can’t control anybody else, you can only control yourself”. Many people find comfort in this quote. When they feel powerless, it reminds them that if nothing else, they have the power to control themselves. However, not everyone has this luxury. I’ve lived the majority of my life with Tourette Syndrome, a disorder where you say and do things that you cannot control. For people with Tourettes, it’s more fitting to say, “you can’t control anybody, not even yourself.”

While the majority of the time, this isn’t the case, people with tourette syndrome don’t always know that they are ticcing. It’s hard to control something that you don’t even realize you’re doing. This is something that I learned right off the bat.

Every year during winter break, my family takes a trip to Colorado to ski and see our cousins. We had just come back from a long day on the slopes, when out of the blue, I started moving like crazy, facial spasms that looked like convulsions- and making strange noises- like “eh” and grunting. I didn’t notice, but my father did. He started to get worried, thinking that I was having mini seizures. He watched me like a hawk until it finally stopped, which wasn’t until I went into a deep sleep later that night. When he was sure that I was done, he called my grandfather. He’s a neurosurgeon, so my Dad wanted his opinion. Nervous that I had something life-threatening, like a tumor, my dad described what had happened and sent my grandpa a video of me that he’d recorded earlier that day. My grandpa assured my father that I wasn’t having seizures, but wasn’t able to tell him what was going on. These episodes continued for the rest of the trip. When I got home, my grandfather examined me, just to be sure. There was no tumor.

Not knowing what was going on, my parents took me to Beaumont hospital to get a full evaluation. The doctors did a battery of tests; blood, physical examination, EKG, the works.

We got the results, and my parents were immediately relieved: It wasn’t anything life-threatening. But, they were concerned to find out what was going on. Within a few days, I was diagnosed with a tic disorder. And, roughly a year later, I was diagnosed with Tourette Syndrome.

Upon finding out about my Tourettes, we went through a battle of recommended medications and treatments. None of them worked, and they all had negative side effects. One gave me a bad short term memory. I became a below average student when I began taking it, and only returned to normal several months after I stopped. A different one made me groggy. Another had no effect at all. On top of that, I always built up a tolerance. Eventually, I just stopped taking meds for it.

I was having a tic attack. I couldn’t explain why, but this time it was worse than the others. I went to the office and called home. Before I had the chance to get out any intentional sounds, my mom was on her way.

When she arrived, I was exhausted and dripping with sweat. I wasn’t in a bad mood. I was used to not having any control over my body, but I wanted to stop. This was by far the worst my tics had ever been.

I ticced the whole way home. I’d clench my stomach, wooh, shriek, bark, and grunt. I’d throw back my head, crack my knuckles, and cross my eyes. While these were my normal tics, they were amplified tenfold. Nobody knew what to do. Soon, my mom had made her decision: we needed to go to the emergency room.

We called the hospital, asking them to prepare a room. They told us that we had to wait like everybody else. “They’re not going to want you in the waiting room,” my mom said to me. She was right. Almost immediately after arriving, they ushered me into a room. I was loud.

The only thing that the hospital could do was put me out with a drug called thorazine. The problem was that it’s a heavy drug. They were concerned about whether or not they should give it to me.

We called my dad. I could barely speak. I was in a good mood, but I’d been going for hours and was exhausted. Hair soaked with sweat, my core hurt from constant clenching and unclenching. I told him that I wanted to stop. So, they decided to give it to me.

I fell asleep pretty fast. Once I was out, my tics finally stopped. The next thing I remember is waking up a couple hours later. My mom helped me get dressed and they wheeled me out of the hospital. I was barely awake. I got in the car, fell asleep, and woke up when we got home. Immediately, I went downstairs and fell asleep in my brother’s room. (They didn’t want me to be alone.)

Tourettes is related to hormones, so it tends to get worse during puberty. When I started sixth grade, I was ten years old. Right around the age that puberty tends to start.

For the first few weeks, I was fine. My tics were a little bit worse, but they always are at the beginning of a school year. It was nothing out of the ordinary. However, three weeks in they got worse. Much worse. My tics had increased drastically and I began having tic attacks daily.

Every day, I would go to a class or two but have a tic attack before I even made it to lunch. Whenever I had one, I went to conference room A, called my parents, and went home for the day. After only a couple of weeks, it was decided that I was too “disruptive” and unable to function to be in a classroom.

The school set me up with the district’s online education program, but it was confusing and hard to manage. In addition to that, I had no motivation. I would have rather watched The Vampire Diaries than read about the sun’s rays or learned how to calculate percentages. I had all the power but what I needed was structure.

I was an average student before I left, but after roughly one semester at home, I had only completed a small percentage of what I needed to. I wasn’t learning. My parents met with the school and decided that, for the sake of my education, I had to go back.

When I returned to the classroom, I was months behind and didn’t know any of the material. My education had been put on hold, but my peers’ had gone on without me.

I was placed into an academic help class, and spent the rest of the year slowly working my way back up. By seventh grade, I had not only caught up, but I began to get A’s.

When I was in daycare, I never slept during nap time. So, they put me in Spanish class with the preschoolers. I’ve been learning Spanish ever since. When I left in sixth grade, I was removed from the class.

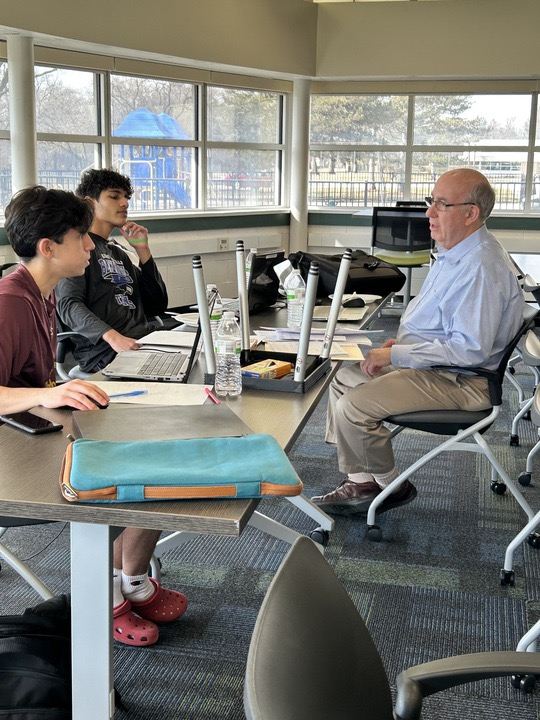

Half way through seventh grade, I went to Sra. Rodriguez, and figured out what I needed to do to rejoin. She gave me a textbook, and for two weeks, I worked with my tutor. We studied for hours each night, learning the entire 6th grade curriculum over break. It was hard, but it paid off.

The next semester, I was removed from my academic help class and placed back into spanish. I had trouble at first, but I worked hard and ended up with an A in the class. I continued with Spanish and at the end of my 8th grade year, was recommended to take junior level Spanish in 9th grade.

That summer, I returned to G.U.C.I. (Goldman Union Camp Institute), the Jewish camp that I go to every year. This year, they told us that a comedian with Tourette Syndrome would be performing, and I couldn’t believe my ears: I’d never met anyone else with Tourettes.

The time came for her performance, and I was ecstatic. She walked up and introduced herself to the group as Pamela Rae Schuller, a 4” 6.5’ mental health advocate and comedian with Tourette Syndrome. Right away, she began with the jokes. There wasn’t a single person there that wasn’t laughing, including me.

She told jokes through her stories. While some were sad and some were not, I related to each and every one. In some way or another. She told a story about a time when school had just let out and she was walking on the sidewalk. She had a tic where she crossed her eyes, causing her to be unable to see where she was going. She tripped, breaking her ankle.

Later that week, after relentlessly badgering my counselors to set it up, I was able to meet with Pam one on one. She came to do a program for my cabin, and arranged for us to have a couple minutes to talk beforehand. We sat outside and talked until we were out of time. For a couple minutes, we talked about Tourettes. We exchanged quick stories and experiences, and talked about the progression of our tics. But we also talked about our shared passion for the arts, our lives, her career and my career plans. We found that we are similar, but weren’t able to learn too much about each other. We only had ten minutes.

However, talking to her was one of the most important moments in my life. This was the first time I had ever spoken to someone with Tourettes. Having never met anybody else with it, there were times that I felt like I’m the only person in the world with this disorder. That’s why meeting Pam was so important to me. It showed me that I’m not alone.

Before I knew it, I was in highschool. First trimester of freshman year. It was fifth hour, the last class of the day. I sat at my desk, listening to my teacher, Mr. Kong, explain something about math. Well, I tried to listen. I tried to ignore what was going on with my body and focus. But on days like this, days where I can’t stop or hold it in, days where my tics are worse, it’s just not in the cards.

I was too busy throwing back my head and rubbing my neck to soothe the pain, to pay much attention. I thought- I hoped that it would go unnoticed, that nobody would turn around to look at me and that Mr. Kong wouldn’t make eye contact, but I’m glad that it didn’t. I’m glad that someone noticed.

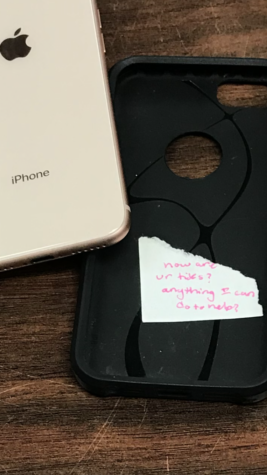

My friend Haley, who sat across from me, ripped the corner of a page out of her notebook, scribbled something down, and passed it to me. A note, asking how I was and if there was anything that she could do to help. I read it and felt strange. Nobody had ever asked me that before. Usually, I just get a stare or the obvious attempt at ignoring it, but she had cared enough to make an effort.

When I read the note, I became acutely aware of my tics, and began to suppress them even more. Not because the note had bothered me- In fact, I didn’t know how I felt about it. To be honest, I still don’t know how I feel about it.

But, I just don’t feel comfortable ticing in front of other people. I’m always ticing, so I’ve gotten used to it., but I still don’t like it. I don’t like feeling like everybody is watching me, like they’re listening and thinking about me and my tics. But, like I wrote on the back of the note, before passing it back to her, “Thanks, but there’s nothing you can do. :)”. Which is true. When it comes to tics, there’s not much anybody can do. At that moment, there wasn’t anything Haley could have done to help me. I’m just glad that she asked.

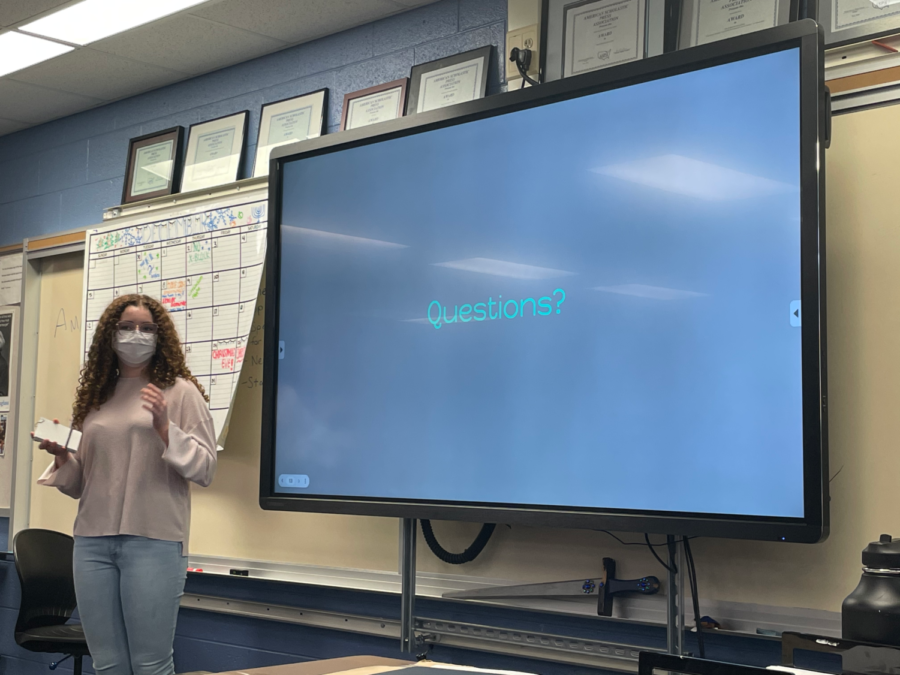

It all started, around second grade, when I was going to a small private school where everyone knew each other. When I got my tics, no one cared. But, when I transferred to a public school in the third grade, nobody knew me. I was teased and made fun of. This was the spark that led me to create a presentation, teaching my peers what Tourette Syndrome is.

On the first day, I went to school and ended up telling my classmates that I had tics. Being third graders, they had no idea what that meant. With such easy access to technology, they decided to google it. Only, they didn’t google ”tics”, they googled “ticks”. And what did they find? Bugs! For the rest of the day, they made fun of me and told me that I had ticks. I tried to explain, but they wouldn’t listen. That afternoon, I went home crying to my mom, telling her all about how “they told me that I had bugs!” She asked me what I wanted to do, but I didn’t know. She said that they just didn’t understand, and asked if I wanted to explain it to them. I did.

We created a handout explaining what tics were. (By we, I mean she made it and I told her what did and didn’t belong.) We printed it out on mint green paper and passed it out to my class the next day.

From then on, they had my back. If someone ever said anything, they stuck up for me. So, every year I give a presentation on Tourettes.

Over the years my presentation has evolved. Since the document was made for third graders, it needed to be tweaked. The next year I made a poster and slideshow. But it was still targeted towards little kids. So, the summer before my Freshman year, I started from scratch and created a new presentation.

While there are times where my tics are bad, my tics aren’t nearly as severe as they used to be. I’ve learned how to navigate life with my tourettes.

Sometimes it can be hard, but I wouldn’t get rid of it if I could. Tourettes is a part of me. The experiences I’ve had because of my Tourettes have only made me stronger. It’s made me who I am today, and I wouldn’t be the same without it.