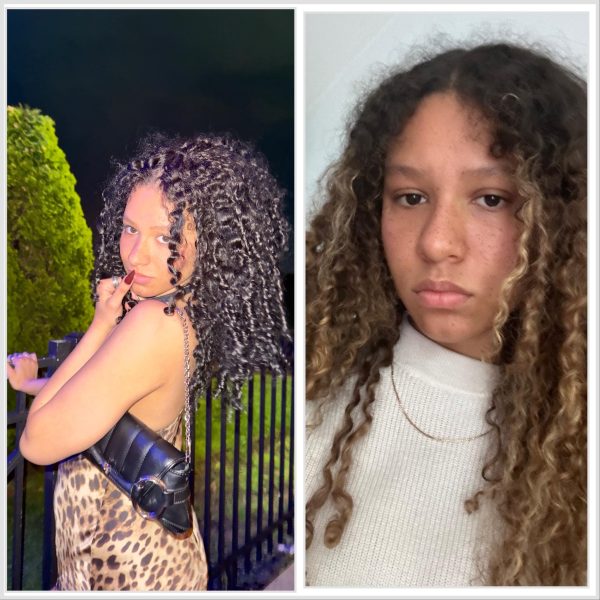

I was eight the first time I wished I could change my skin. Standing in front of my pink bedroom mirror, I stared at the poster of Princess Tiana and imagined what it would be like to have her deep brown skin and smooth curls. But the reflection staring back at me had frizzy brown hair, my soft hands covered my cheeks, flushed from tears, and a question I couldn’t shake: how could I ever be a princess when I didn’t look like one?

I stared into the mirror at the tangled mess of curls erupting from my head — wild, stubborn, lion-like. The brush crackled through my dry hair, each stroke a battle. It sounded like the curls were fighting back, resisting the plastic bristles that snarled and snapped at every strand, as my mom brushed my hair. Reaching up, I grasped her wrists through pain, squeezing the tool that I called a monster. Once I grabbed the brush in my hands, I would throw with all my strength; the brush would fly across the bathroom tile, scratching again the tile to the bathtub. Screaming in tears as my mom pulled my hair back, slicked it tight, and brushed the ends. My eyes were red with swelling underneath the lower eyelid, puffy and soft like a pillow. Every day I would look in the mirror and see the same moment over and over.

I was just a figure in the mirror that felt haunted by its reflection. On one side of the glass stood a girl with puffed-up curls, wild and free. On the other hand, tears welled in the eyes of a lion in spite of her reflection, who couldn’t be tamed, not because she was strong, but because she was tired of fighting. Tired of wanting the hair she didn’t have — hair that lay perfectly flat, perfectly still, unlike her own.

I was brushing up on something. To make my hair smooth. To make it better. But no matter how hard I tried, I didn’t get my mom’s silky, straight hair that shimmered in the light. I got something else — something I thought was ugly. Something that made me different in all the wrong ways.

And I couldn’t help but wonder: If there was no space in the princess’s palace for a girl who looks like me, then how could I find space in the real world I face every day?

But this was the challenge I had to live through. A challenge I still face today. One that’s all too real for so many young girls who don’t see themselves in the worlds they grow up in. This is my story — how I’ve learned to shift my perspective, to love myself for who I am, not what the world tells me I’m supposed to be.

I first realized that my mom’s and my dissimilar resemblance stood out when we stood outside a Trader Joe’s, our Girl Scout cookie table set up with a bright blue cloth and carefully stacked boxes. I wore my vest proudly, two braids falling over my shoulders. Another troop approached with their table nearby, their sign-up sheet held in hand. I smiled and waved as we crossed paths. A mother, her blonde hair catching the sun, looked down at me with curiosity.

“Oh, does she go to your school? Do you know my daughter?” she asked kindly.

“Yes,” I answered, standing beside my mom on the curb.

“Is she adopted? Where did you get her?” Sharp, casual, and cutting. She handed me a box of cookies, her voice light, her smile unchanged, as if nothing had happened. But something had. Her words dropped like stones in my chest. I didn’t understand why they hurt so much. I only knew they did.

“But you don’t look like your mom,” her daughter said in a wide-eyed voice. And that’s when I started to wonder — was I adopted?

I asked my mom that night. Not because there were no baby pictures. Not because I didn’t feel loved. But because something didn’t match. My brown skin didn’t look like hers. My hair didn’t look like hers. And no one around me—not the movies, not the books, not the princesses—gave me an answer for who I was. What box do I belong in?

“You should’ve never had a biracial baby. People are going to treat her badly,” my grandfather said. Remember the day in fifth grade when my grandfather told my mom this in front of me, and those words stuck with me. When I was born, they weren’t happy that I was both Black and White. This didn’t make me ashamed of my skin, but because, for the first time, I felt like my very existence was wrong. Like I wasn’t supposed to be here. Like, I didn’t belong anywhere.

On my dad’s side, it’s a similar story. My grandmother doesn’t speak to me because my mom is white. She doesn’t consider me Black enough and is disappointed by how light my skin color is.

I moved to Kalamazoo, Michigan, in second grade, where I was the only African American or student of any ethnicity, and the first moment I really realized this difference in culture was when I was sitting in a classroom in third grade. During read-aloud, girls would comb each other’s hair with their fingers, brushing through like silk on a spindle — seamlessly and effortlessly. Two things my hair did not do without water and a hairbrush.

“Hannah, can we brush your hair?” Lexi, a girl in my class, asked repeatedly while I was sitting on the carpet as I looked down at the colorful rug that highlighted the colors of the rainbow — a significant pattern that stuck with me for the rest of my life.

“My mom said not to let people touch my hair. I just washed it.” I turned sad every day, with hair that was fresh and slicked back, tightly braided.

“Well, I just want to see. I’ve never brushed curly hair before. It would be so fun! Because your hair is so long, you could make a super braid. Can I French braid it?” She said, grabbing out her hair brushes, sitting behind me, close, crisscrossing, applesauce on the floor with her hands touching my hair.

“Sure,” I said eventually. I gave in, with the condition that it wouldn’t hurt.

“Oh, it won’t hurt, I promise,” she said, grabbing the black scrunchie that pulled my hair tight in a slicked-back style and unraveling it. My hair fell out of the braids — chunks of curls falling down to my waist. The brown streaks highlighted every tangle and every rat’s nest that was in my hair and seemed to glow as the flyaways reflected against the sunlight. Then she grabbed a brush out of her bag and started brushing.

My head leaned back tightly. My neck crunched. I closed my eyes and bit my lip from the pain. My hands pressed into the red carpet as I stared down into my lap. And then there was a knot. My hair wouldn’t separate where she wanted to braid.

“Ow, ow, ow,” I said quietly as tears welled in my eyes. My voice steadily started to get louder, but she wouldn’t let go, still untangling my dry, curly hair, ripping the curls as the brush scratched the coarse ends, biting and snarling at the once slicked-back style.

“I wish I had curly hair,” she said. And in my mind, I knew that wasn’t true.

I knew it wasn’t something she really wanted — just something she couldn’t have.

“Done,” she said, letting go of her tight grasp on the hairbrush. I ran to get up as my feet could not get out of the criss-cross applesauce position quickly enough. I ran to the restroom and looked in the mirror, and once again, I didn’t see the silky hair that I longed for. Only a fluffy mess, shaped into a braid. Forced into a braid.

And I was almost mad at my hair.

Why can’t you just behave? Why can’t you just be like everyone else?

When I moved back to Birmingham, I figured the city was supposed to make this feeling of being an outcast go away. But I saw life from other people’s perspectives outside of my own house: just Black and White.

But I was neither. I was in between. And that seemed to be an idea that those around me couldn’t accept. Especially when those who looked at me with frustration couldn’t identify it by just looking. The first few times were in a nail salon, where the lady next to me went through a list of different ethnicities I could potentially be mixed with.

“Or let me guess — is your mom white? Is your dad Black… Maybe Mexican?

Only tell me if I guess correctly.”

“Oh, my dad’s African-American, and my mom’s White with red hair,” I said.

“That’s a great mix. I could have guessed that just by looking at your freckles and your nose!” she said as though she had slapped the buzzer on a game show. Like I was some sort of smoothie to be mixed up with or a flash card that is on national television waiting to be guessed.

At school, the constant question of whether I was Hispanic or Hawaiian was another one I often got asked. Being objectified — not for my heart, but for my appearance—became a fear that always followed behind me.

“You look more Black than you do White.” During my presentation in school, a girl yelled that out.

“Oh, your curl pattern? You’re not really Black —you’re whitewashed.” A girl said when my parents divorced and I lived with my mom, when people would find out, they would say that’s the reason I speak, dress, and act White, just like a “White mom.”

“You’re not Black or White; you’re splotched.” That was a description I first heard in fifth grade, when kids said my skin looked like a banana peel—bruised with freckles, patched with Black and White.

“Mutt.” At school, kids called me this, laughing at the idea that I wasn’t “one race or the other.”

Was I being bullied because I wasn’t “Black enough” or “White enough”? The truth is, I never felt like I could figure it out.

First reveal of the red-dyed hair—vibrant, fresh, and adventurous, signaling a new phase in personal style.

Photo 6 — April 20, 2024 (Concert)

Candid concert moment with vibrant curly hair, still holding traces of earlier red dye, full of energy and expression.

Photo 7 — May 10, 2024 (Prom)

The prom look showcases straight hair after the faded red dye, subtle tones and smooth hair, but dry due to heat damage during the transition. (Hannah Gray)

I went to my mom’s hairstylist, and she cut off eight more inches than I asked for—my hair, once flowing down to my waist, now only reached my ears. I didn’t know what to do with it, and I felt like I didn’t look like a girl anymore. My hair, now curly and cut short, felt too masculine for me. I started to believe I had to pick a side. I needed to choose who I was, and this confusion started to solidify when I developed my first real crush in ninth grade.

As I sat in that classroom with him, I hadn’t yet come to terms with my hair, my appearance, or even the growing realization that I was struggling with my identity. Every day, I tried to tame my hair into a tight bun or braid, hiding my curly bob, terrified that if anyone saw my hair for what it really was, I wouldn’t be considered attractive or feminine enough for someone to like me.

I watched the other girls in the class, the ones he spoke to, the ones he seemed interested in. I sat in silence, overwhelmed by the fear of showing who I really was. I saw a girl with blonde hair who he talked to every day, and in my mind, I thought, He could never like someone like me. I don’t look like the others. I don’t fit in.

That crush faded quickly, but it left an impression—a fragment of my self-worth that slowly chipped away, like a puzzle piece that couldn’t quite find its place.

Then, 10th grade arrived, and I was desperate to make an impression. I decided that to do so, I had to shed the part of me I thought he wouldn’t like—the part of me that was Black. So, I begged my mom to let me bleach my hair.

My dad was upset and asked, Why do you need to bleach your hair? You don’t need to change it. But I went ahead and did it anyway, without telling him. At first, I only had a few streaky blonde highlights, but within three months, my hair was completely covered in bright, sun-kissed highlights. But even that wasn’t enough.

I wanted to have the straight, silky hair that I’ve always wanted, so I asked for Christmas to have the Dyson Airwrap—the thing that could give me my dreams that I longed for. The thing that could make me fit in. Girls could finally brush through my hair. I could put my hair up in a messy bun, and it would look effortlessly cute and not like a frizzy nest on top of my head. The thing that could finally grasp a little bit of attention.

And so every week, I would take my blow dryer to my hair, and I would put the heat on three, watching the red dots glow as I held the stick to my head, and my hair slowly turned straight. The curl pattern got stretched out like a Slinky, slowly losing. Often, the heat would accidentally get too close to my scalp, and it would burn. I would close my eyes and say, This is the price I pay to feel beautiful inside.

As I looked in the mirror, I slowly saw that part of me fade away as my head was slowly covered in the straight strands that I had longed for my whole life, falling to my shoulders like gold strands, thin and wispy. Crestfallen, wondering maybe if it would change how people looked at me seeking validation.

Would I be more attractive? Would I be someone who would be cuter, have more friends, have an identity that I could fit into, and hide the secret that I never had curly hair that was brown at all? No one needed to know.

I started to straighten my hair every single week, with touch-ups every single day. The flat iron would run through my hair on top of the blowout, steam releasing as the bathroom mirror fogged up again, slowly turning faded grey, and my cheeks turned pink from the heat that ran through my hair. My foot ran against the crack of the door as the ridges cut my heel, allowing the fan’s crisp air to run through the bathroom. My hair was straight 12 months out of the year, and it was blonde. No brown roots to show, but platinum white to the root. And now I got more laughs, the attention—everything that I thought I wanted.

I started to think my hair was natural—naturally blonde, naturally fried, naturally straight and dry, not special. My tan complexion and the freckles I had on my face secretly gave away the fact that that wasn’t really me. The dark in my eyes that was a tunnel to my true self gave away the fact that the blonde was only a persona that I created. The smiles, laughs, giggles, and happiness—it was all a false idea. The fake lip gloss applications as I looked at the mirror, the hair twists. The act of being blonde was natural, a mask that had sealed so tightly.

“You have to let it go because you’re only on this earth for a short period of time, and this will follow you your whole life, but if you let it bother you, it will hold you back in med school, in college, and stop you from getting to where you want to be.” My dad said.

It seemed like everywhere I went, the comments followed behind. Being called a name because of how I looked or being treated differently or always having the feeling that I want to be Black enough or White enough, but the feeling of anger came over me not because of just the things that were said, but because no forgiveness or embarrassment washed over their faces because they never knew what they said was wrong.

Forgiveness does not mean forgetting, which often gets confused, but it means to recognize ignorance and let it go, but with that, hold them accountable, let go of your anger, and let them hold it with their hands wide so you can be free. Because you have the power to let power go.

I would take a shower, and my hairbrush would be covered with straw of hair that almost looked like a bird’s nest, highlighting the white and the blue on the brush in the bristles in contrast to the parts of the roots from where the blonde had grown out.

As the blonde grew out, I started seeing Instagram pages of girls with black hair, tan skin, dark eyebrows, and freckles. I would imagine myself mirroring that in my reflection, having my dark, curly hair. My eyes would shift from the photos to my reality of the hairbrush in front of me, with clumps of hair that would dry, a bird’s nest intertwined between each bristle, and brassy hair left on the brush falling apart and slowly being intertwined with the bristles. My face turned in shock, and my hair slowly got thin, and my ends turned into little see-through, transparent pieces— almost like frizz again.

First reveal of the red-dyed hair—vibrant, fresh, and adventurous, signaling a new phase in personal style.

Photo 6 — April 20, 2024 (Concert)

Candid concert moment with vibrant curly hair, still holding traces of earlier red dye, full of energy and expression.

Photo 7 — May 10, 2024 (Prom)

The prom look showcases straight hair after the faded red dye, subtle tones and smooth hair, but dry due to heat damage during the transition. (Hannah Gray)

I grasped the bottle of shampoo and held my hands over my eyes, crying, balancing the purple shampoo for the clumps of hair on the brush. As many times as I ran the flat iron over it, it wouldn’t lie down because it was dead. I put the flat iron down against the rubber lining in the cabinet and watched it go into the drawer, watching it fade as the drawer closed inwards like a cascade, and with it the idea of the split personalities—split racial division in my head—went away. With this false idea that I could only be one race or one ethnicity, it was finally put into a drawer, locked away.

I started using hair oils, and I finally went to the hair salon and got my hair dyed black. And as I watched the grade halfway through the year, when I finally had the courage to, because I no longer felt the need for external validation but now found those features beautiful, and the things that make me me—I accepted them.

When I got my hair dyed black, I watched it cover my hair as my blonde slowly faded away. And as that happened, my hair went from platinum white blonde to the darkest shade of black that you can get your hair dyed. And my roots finally matched the rest of my hair, and my hair finally curled the correct way.

I showed up to school on the first day of 12th grade, nervous to show who I really was—my hair, my tan skin, my freckles. It wasn’t just a look; it was a package of all the things that make me me. And with that came the decision to stop trying to fit into the convenient box others expected me to fit into.

That first day, my dark strands of hair coiled in a thick bunch falling to my shoulders, my ends curled together, and each strand stood in its place. For the first time ever, I felt confident in who I was. Because I wasn’t pretending. There was no blow dryer. No straightening iron. No steam clouding up the bathroom. Just a bonnet and a bottle of gel.

When I looked in the mirror, I saw the girl I used to be—but this time, I wasn’t ashamed of her curly hair or any of the things that made her different. I was finally starting to see beauty in the patterns of my curls and the tone of my skin, but also, the most important part, my heart.

People think it’s an exaggeration. How could something like being biracial affect your life that much? But it’s not just about skin color. It’s about how people perceive you, how they treat you, and how they define you before you even open your mouth. But with that challenge comes a gift: the ability to see beauty in all kinds of differences—in light hair, dark hair, every skin tone, and the features that make each of us unique. And perhaps most powerfully, it gives you the freedom to step outside of others’ expectations and comments and hold the gift of deeper, lasting confidence in your hands and your hair.