At the end of Ms. Lauryn Hill’s 1998 song Lost Ones, a keyboard synthesizer faded out into the ambiance of a New Jersey elementary classroom. Ras Baraka, an activist, led the students in an improvised lesson on love.

“Alright people! I’m gonna write something on the board. Let’s spell it. First letter!”

“L-O-V-E,” the class spelled in tandem with Baraka.

“What’s that?”

“Love!”

“What?” Baraka yelled.

“LOVE!” the children shouted, even more enthusiastically.

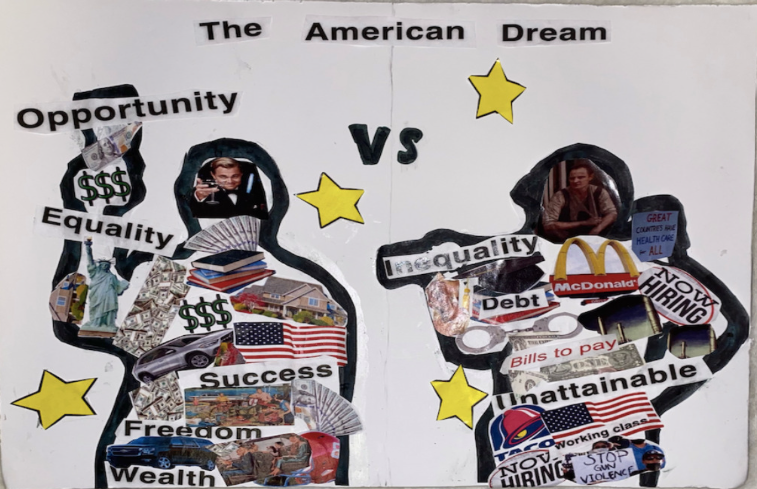

Love is loved. Next to wealth and beauty, having a significant other is viewed as one of the three most important investments one can have. Romance novels make up 1/3 of bestsellers worldwide. The amount of references to The Notebook in the media rivals that of the Bible. The average American has an average of eight partners. So love is loved, right?

Unfortunately, love is hated as much as it is loved. Loving love hasn’t always been—and may never be—the standard. Queer and interracial relationships come under fire by bigots. Really, it might be more the idea of love that we so unwittingly romanticize.

One of the best recent fictional portrayals of love is season two of Our Flag Means Death. Although it includes the basic empirical formula for romance—tension, copulation, passionate affairs—it exceeds one’s expectations of a typical romance with its considerate approach to queer love and cunning humor on domesticity. In other words, it makes viewers reconsider their idea of love.

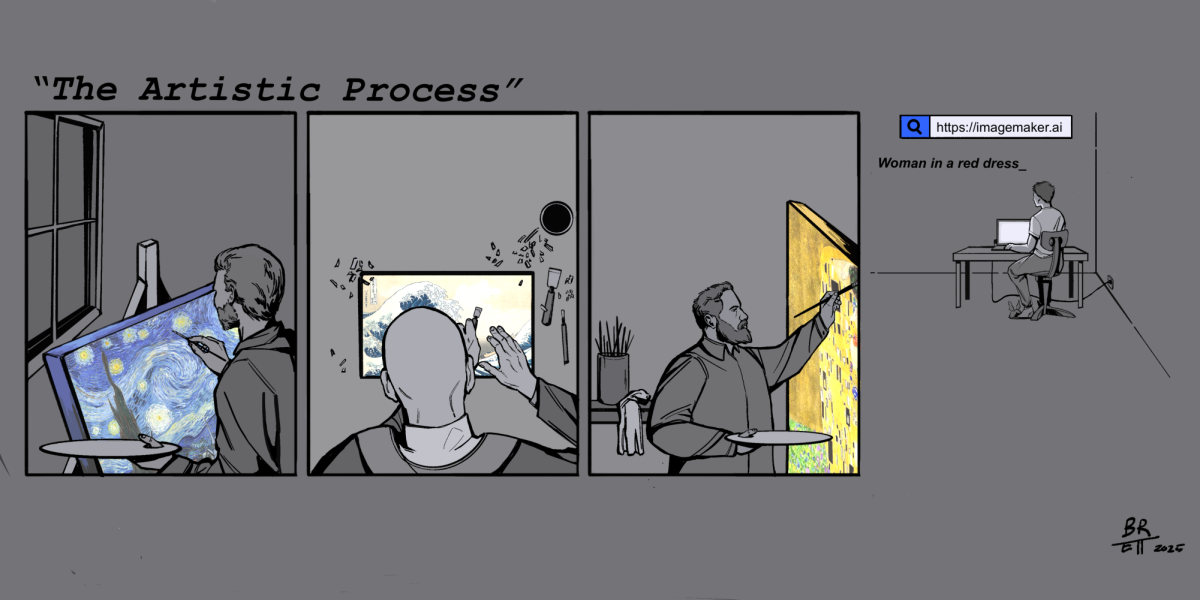

A recent notion that has made many reconsider our idea of love is a direct opponent of Our Flag Means Death: queerbaiting.

“I don’t understand why the pain and suffering of queer people has to become a cash grab. It’s incredibly insensitive,” junior Sanuthi Wickramasinghe said. Along with rainbow capitalism, which capitalizes off of queer labor, queerbaiting—a marketing technique in which a character’s sexuality is hinted at but not discussed—is detrimental to queer youth because it leaves them feeling unfulfilled; like they will experience queer romance as it is reflected in today’s most popular shows.

“Both are for profit, if you think about it. If a show queerbaits, they’re trying to hit a demographic,” senior Nia Daniels said. And she’s right. Executives who queerbait don’t care about their target demographic: they only care about the money in their queer audience’s pockets.

“Rainbow capitalism can be avoided by purchasing from authentic small businesses,” junior Patricia Mitchell advises.

But Our Flag Means Death is unique in that it is one of the few shows with queer characters that does not queerbait. Executive producer Taika Waititi believes that “humans have all got some degree of queerness to them” and consequently places importance on telling queer love stories. Telling these tales is integral to queer culture. Representation matters: it directly impacts how accepted someone feels about their sexuality, and also how accepting others are willing to be.

Homophobia is, unfortunately, not a recent notion. Throughout history, lovers were forced to keep same-sex relationships hidden. History is defined by the “winners” (or rather, the oppressors) rather than the subjugated, so there is not much queer history documented in our world today—but homosexual relationships in history were more common than history class would have you think. “Boston marriages”between women, and intimate letters exchanged between men, prove that homosexuality has always been here, even if societal standards forced lovers to keep quiet.

Pirates, however, were known for rejecting societal standards. Scandal was their standard. This meant being violently nonchalant about same-sex relationships, especially during the Golden Era of Piracy (c. 1650-1730). Some crewmates even had financial unions called “matelotages” in which one mate would take possession of the other’s assets should they die. Still, civil society and pirates weren’t complete opposites. Pirates also had to establish a caste system. Younger pirates traded for trust and respect via sexual favors or matelotages. Captains often made their lovers first mate. Homosexuality was used as a tool for ascending the social ladder; it was viewed as not only a righteous symbol of love, but a totem of power.

But does power equate to love? Yes! Historically, pirates in the 18th century would have received little foul for pursuing a relationship. Two of the show’s major characters, Edward “Blackbeard” Teach and Stede “Gentleman Pirate” Bonnet, fall in love. And they are both men. In an accurate tandem, the show’s crew has no issue with Teach and Bonnet’s relationship. However, Our Flag Means Death has a modern audience, so queerness is initially presented with a shameful skein to capture the angle of self-homophobia.

Teach’s beard is a metaphor for internalized homophobia. Each time Teach grows closer to Bonnet, his beard becomes less significant to him and is shaved off. He grows it out (or insanely smears a five o’clock shadow back on with charcoal) whenever his gay identity becomes too much for him. Not to mention that “beard” is a slang word for a woman who dates a gay man as a cover for his homosexuality—so Teach’s beard metaphorically is a cover for his gayness as well as physically.

In fact, Teach’s whole season two crew represents oppressive homophobes while Bonnet’s crew represents radical queer acceptance. They are othered from Bonnet’s crew aboard The Revenge, described as “off-putting” and “feral.” Their disparaging mindsets and overwhelming toxic masculinity is rehabilitated with polite humor and the Revenge mates’ quiet quips.

Teach’s first mate Izzy Hands is apprehensive about his gay identity—so much so that he would rather eat his own toes than accept himself. Eventually, he embraces his identity as a gay man by performing in drag to La Vie en Rose. Dramatic, right? If there’s one thing Our Flag Means Death knows how to do well, it’s character progression. Through effort, rehabilitation, healing, and most importantly the motif: love is possible.

“Real love takes time and effort… Love isn’t easy. It takes time, commitment, understanding, forgiveness, and loyalty from both people,” Mitchell said. Love is not the benefactor to all solutions, but rather the result of effort.

Two characters, Jim Jimenez and Oluwande “Olu” Boodhari, experience a friends-to-lovers relationship arc over the course of the first season. After being separated for the months in between, they neglect to rehabilitate their romantic relationship.

There’s a distinct parallel between Jimenez and Boodhari and Teach and Bonnet: they were both separated for a long period of time with the choice to revive their romance or let it fall into friendship. Senior Gabrielle Stallings puts the phenomenon into words perfectly.

“I think love can fizzle out. People wake up different every day. You can be in love with someone and one day you just… don’t [love them] anymore. You have to choose to put in the work for that. It’s not just something that’s gonna be there every day. I think it is a choice if you really love someone. It’s definitely a choice as far as how much energy you put into it, how much time you put into it, and going back to it even when it’s hard,” Stallings said.

Where Teach and Bonnet made the effort to love each other romantically, Jimenez and Boodhari fell in love with other people and let sleeping dogs lie. They still love each other in a platonic sense—they’re “like anchors for each other,” as Jimenez says, but they don’t want to put in the effort to be a romantic couple anymore. Our Flag Means Death doesn’t devalue Jimenez and Boodhari’s friendship, and that’s what’s great about it. Love doesn’t have to be romantic. What even qualifies as an act of love, anyway?

According to Daniels, it’s “Being genuine. I feel like there’s a lot of nice things you could do for people, but a lot of times that could be transactional. I give them this and they give me that in return, you know? But that’s not love. Love has to be genuine; not expecting anything back. Doing it out of the kindness of your heart, not whether or not you’re getting something back.”

Junior Juno Saulson adds “Grand gestures like… buying the right to a plane for an hour and flying over your spouse’s head… that’s an act of love, but I also feel like that act of love can be something as simple as remembering somebody’s favorite food and then getting it for them. It can be something as small as remembering someone’s favorite color or just a past conversation, or buying something for someone unprompted or doing a chore for them unprompted.”

“It’s also just this innate feeling that you can’t describe,” senior Ronnie Newby said. By these students’ standards, the two main relationships portrayed on the show are keystone examples of love.

All of Bonnet’s actions toward Teach are genuine. He makes sure that Teach always feels comfortable and has a place on his ship, allowing him to borrow his clothes, sample his teas, and go on (somewhat unsatisfactory) treasure hunts. Bonnet never expects anything back from Teach, but still, Teach returns the favor. Teach is accused of having a “soft spot” for Bonnet—letting him live, going along with his silly quests, entering high society for him, and giving Bonnet constant reaffirming touches and taps throughout the series. Where Bonnet would die for Teach, Teach would kill for Bonnet. By the end of the second season, it’s vice versa.

As far as grand gestures go, Bonnet wrote several love letters to Teach, and Teach staged a coup so they could run away to China together. Bonnet and Teach also prioritize communicating about their feelings, which according to lesbian ex-pirate couple Anne Bonny and Mary Read is “so [freaking] earnest” that it’s comedic.

Love is also an innate feeling that can be portrayed only through things like repeated imagery or song. For that, I refer to Gnossienne no. 5: Bonnet and Teach’s main love song. This plays whenever they are together or are thinking about each other. Thanks to the elegant sound of tinkling piano keys, the viewer gets to experience the same euphoric rush that is known as love alongside Bonnet and Teach. There is also a scene in which Bonnet says to Teach, “You wear fine things well,” which is constantly called upon whenever the two characters are pining for each other. Through these many criteria, one can conclude that Stede Bonnet and Edward Teach of Our Flag Means Death are in the deepest state of compassionate love.

Their love is proven pure, despite what homophobes might think. Our Flag Means Death writes queer characters’ sexuality not centered around their experiences with homophobia, but rather as an unchangeable aspect of their character. First and foremost, they are people. Although it is a fair part of their identity, who they love does not define them. This both affirms people who have accepting social groups and sets an example for those who don’t. They are queer, of color, and figures in history: it’s simply a matter of fact. Their internalized hate and past experiences do not define them. They are queer because it’s who they are, no more to add.

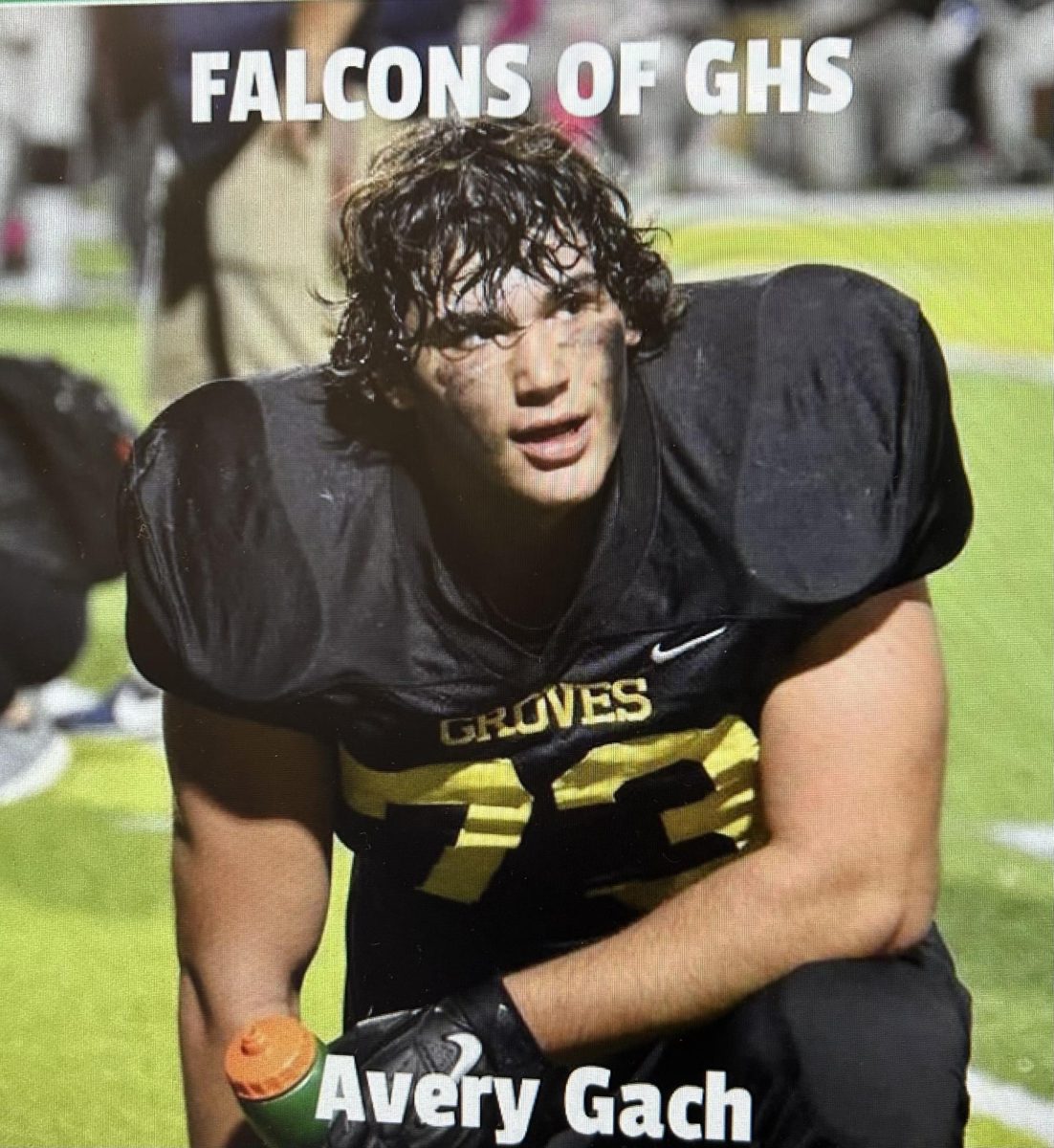

Our Flag Means Death is a love letter to queer audiences—but don’t just take my word for it. I asked some Groves students what they thought about the show.

“I think it’s fantastic. It’s so well done. I love how it’s comedic and it’s still joyful.” senior Brooke Reynolds said. “It actually got canceled.” On January 9th, creator David Jenkins confirmed that the show’s third season was to be dropped by HBO Max. Unless millions of people host an organized protest, the show is unlikely to return for its planned third season.

Sophomore Aaron Hoener says that he “loved the first season! The writing, the development, [and] the characters were all beautiful!” However, he felt the second season fell flat. “The story became a bit rough, and it felt like a lot of the fleshing out that happened in season one kinda just disappeared… [But] the show has great queer and disability representation,” Hoener said

“I think it’s a solid show with a good plot and solid representation. But, I do think that the concept’s a little wonky, especially considering that Blackbeard and Stede Bonnet were both horrible people in real life. I know it’s historical fiction, but I can’t really separate them from each other,” Saulson said. Should we be uncomfortable with reimagining historical figures? Has the “Hamiltonification” of these figures gone too far? Perhaps reimagining them as non-offensive, human characters takes away some of their power. The real Blackbeard and Bonnet—both horrendous people in real life—would take great offense to find out that their most popular adaptation is the one where they fall in love with each other.

“Love is as love does. Love is an act of will—namely, both an intention and an action. Will also implies choice. We do not have to love. We choose to love,” Erich Fromm said in the 1978 novel The Road Less Traveled. This is part of what makes love, and especially queer love, so powerful: choosing to endure hate for one exceptional person.

“We live in a society where queer love is often seen as wrong and to be able to share that love you have to be stronger,” Wickramasinghe said. And Our Flag Means Death does an exceptional job of that.