African American students speak out against restrictive definitions of minority identity

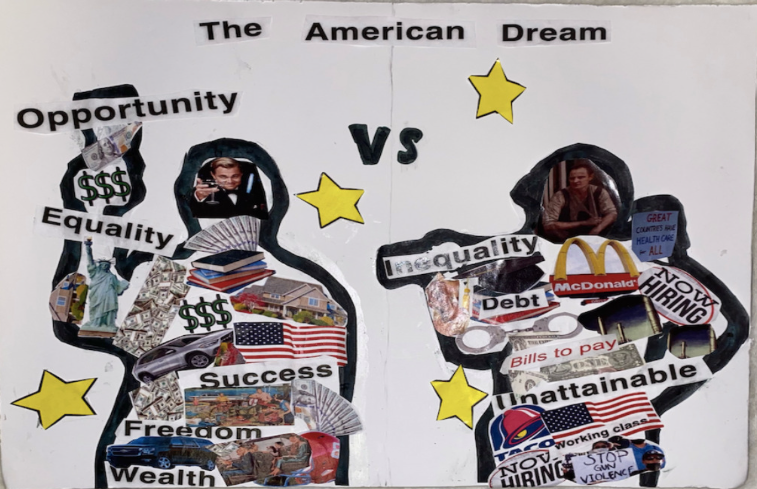

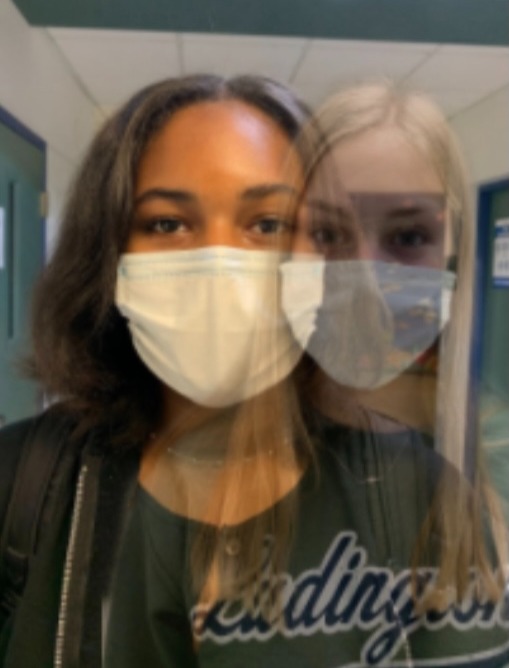

Junior Gabby Pearson and senior Lydia McKeever depict how harmful stereotypes and terms, like “white washing”, have lasting impacts on minority students. You’re basically calling me white washed and that’s really offensive. Many African American students have been called ‘white washed’, like me, Shelby, all of us,” Pearson said, referring to herself and three of her African American friends at Groves.

“You’re not really black.”

A student told junior Gabby Pearson this during her food class freshman year.

“I was like what does that mean, and the girl goes, ‘Yeah, you’re not really black.’ What does that even mean? How are you going to tell me what my identity is? There’s so much behind that loaded comment. One, what do you believe black people are supposed to be? And second, Is there a specific model? No, there is not,” Pearson said.

Pearson says this is just one example of microaggressions absorbed within the minds of minority students at Groves Highschool.

“Another time, I was at my table in health, talking to these two boys about the weekend. I told them I had a function in Detroit with a bunch of black people, and the first thing they said was, ‘Dude, you have to join a gang before you’re safe down there,’” Pearson said.

Listening to the racist words told by Pearson’s classmates left her in shock,

“I was flabbergasted. Why does everyone believe that? There are so many bad stereotypes. Black people are aggressive; black people are in gangs; black people this and this and this. We need to break these stereotypes,” Pearson said.

Pearson believes stereotypes, such as these, only increase the feelings of alienation between diverse groups and communities. She thinks these false claims and harmful words spoken not only prolong the negative connotations from which they are constructed, but also throw salt in the wound to minorities who must suffer the alienation intensified by the ignorant verbiage of someone else’s words.

Junior Shelby Gibson states how schools fall victim to these stigmas which causes feelings of discomfort for all parties. She laments the division between races in our school despite the diversity.

“There’s diversity within the school- but they don’t mix. They don’t mesh well,” Gibson said. “I think it’s subconscious. People tend to not know that they’re doing it. People are just used to being around people who are like them. It’s somewhat human nature, ya know?”

Gibson believes subconscious thinking has often been overlooked when it comes to biases that students have. That people tend to stick to what’s comfortable instead of learning about the unknown. She feels the biases we have, divide us more than anything whether it is intentional or not. With the severance of the school and fewer mixing of groups, the margin of saying something derogatory or insensitive increases substantially.

“You know how many times I’ve been walking down the hall, and I’ve heard someone call something ghetto? I’m just like, they don’t understand the history behind anything they do,” Pearson said.“I feel like we can fix that because that’s the major problem here.”

The term “ghetto” has been linked to the African American community since the early 1900s. As a derogatory term, it was used in cahoots with residential segregation. A dividing line that disproportionately segmented black people into areas of black, low-income homes and further dissented black families and white families. Many individuals saw the term as a stigmatization of black communities, and slander to their reputation for perseverance, independence, and the importance of family African Americans worked so hard to create.

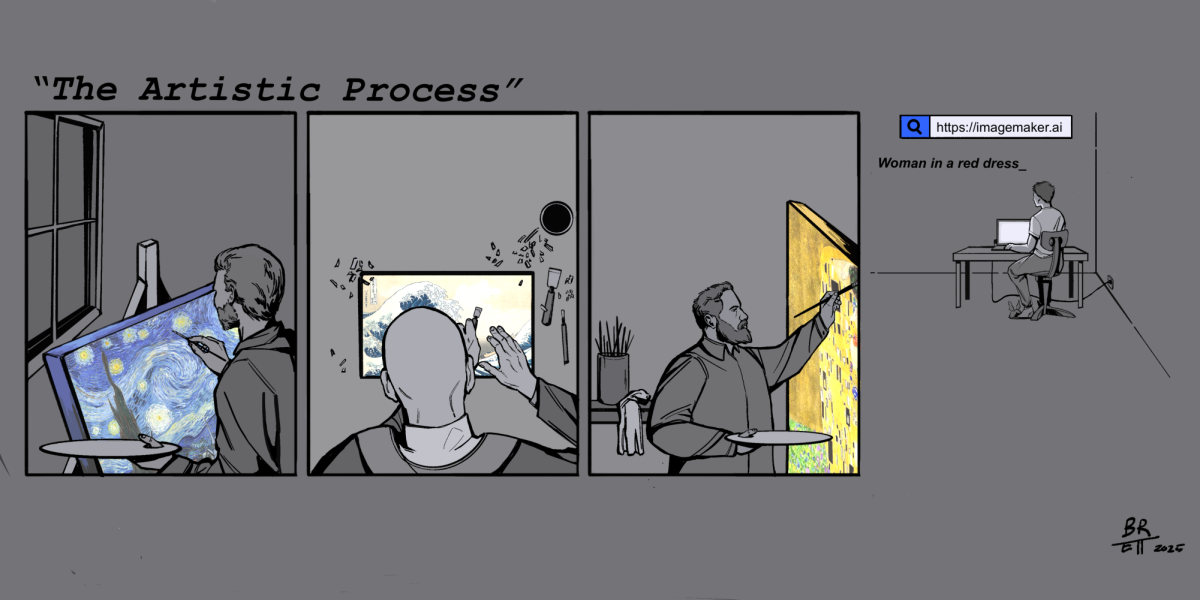

How African American history is taught has resurfaced as a hot debate among politicians and educators; “Critical Race Theory” being at the forefront of those discussions. According to Education Week. org: “Critical race theory”, a concept that, at its core, is advancing the idea that “race is a social construct, and that racism is not merely the product of individual bias or prejudice, but also something embedded in legal systems and policies.” Some argue that school systems that touch on the oppression of African Americans, teach what’s necessary for the students. While others cry out that this is “Critical Race Theory” and argue that this is a way for education to make non-minority students hate America.

“The only time that black history is enforced and taught, it’s glossed over. It’s minuscule, barely grazing the surface. You hear the same historic names from elementary school to high school, figures like Martin Luther King, and people like that. But we aren’t taught about how to not be offensive,” Gibson said.

Counseling department head Norman C. Hurns responded to Gibson’s concerns and expressed his feelings about a school’s role in his children’s education.

“I think that’s somewhat true, and I can understand why Gibson would think something like that, but I’m not counting on Birmingham Public Schools to educate my kids on what it means to be African American in America. So, whatever the school does is extra to me,” Hurns said.

Gibson believes teachers refrain from educating African American history for the comfort of the white children in school. She poses the question, Who is this education for? Is this for the advantage of the African American students or to further educate the white students? Or both?

“Teachers also do this to not come across as controversial,” Gibson said. “With that, the teachers want to have as few complaints as possible. If this little white kid goes, ‘my teacher made me uncomfortable’ the parents are gonna come in and ask if they can make the student feel more comfortable. What people need to realize is that racism isn’t comfortable. It’s not supposed to be.”

Hurns says there are steps we can take to help our schools feel more inclusive for all. Groves does provide outlets for African American students to feel incorporated and established within the school and explained plans for much more in the future.

“ We’ve been doing a multicultural retreat, which will be held again this December. The multicultural retreat is when juniors and seniors of different groups come together, not academic, just different groups. We spend over two and a half days addressing issues in our building, in hopes students can go back to their particular people and now have an insight of these different diverse groups of individuals with contrasting backgrounds,” Hurns said.

Even with our few principles for inclusion already set in place via the multicultural retreat, and clubs, students believe there is much more needed for our schools to reach their full potential. Students at Groves have many ideas of how to bring that dream to light.

“Groves could help us be more inclusive, with clubs and events around the school, for the black youth, so that we all feel more included,” Junior Chris Cammon said.

Junior Paige Williams expanded on that thought.

“I feel like we should have the AACT (African Americans Changing Tomorrow) do more around the school. AACT hosts trips primarily in Detroit, Why can’t we do something for Groves?” Williams said.

Pearson and Gibson highlight, the need for louder voices to connect the diverse groups in our school. How amplifying the words of minorities gives students a greater chance to bridge the divide between various racial groups and realize the dream of interconnected diversity in our school.

“Racism and those little microaggressions happen every day. No one wants to speak up about it, so the school itself is not aware of the subtle racism pervading our school. We could have students, like those who spoke up in this article, present moments where they experienced feeling like an outsider because of their race. Perhaps, at an assembly or incorporate it into a group seminar,” Pearson said. “Beyond school initiatives, I think it mostly comes down to communication between students at Groves. We communicate, but we aren’t able to have those deep conversations that need to be had to help better Groves as a whole.”

They believe words are powerful and a gateway to understanding not only our peers better but recognizing the changes we need to make in ourselves. If people can all take the time to listen, they will be on the correct path to not only understanding certain individuals but providing inclusion for all.

“I think we are moving in the right direction, but I think you guys are the ones that are going to make that move. I do have hope in humanity that things are going to be different. What you guys have experienced and grown up with is different from me, and I think the opportunity is there to bring diverse groups together,” Hurns said. “The power to make minorities feel more comfortable within the school is in our hands and without these changes, we are in danger of not fulfilling that deed, in danger of succumbing to those who are even now trying to push legislation that would silence our educators from teaching students about racial issues in a manner that raises consequences while lowering fears about differences.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Wylie E. Groves High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Elise Wagner is one of the two current Editor-in-chief’s for the Scriptor. She prefers writing over editing, and likes writing investigative articles....